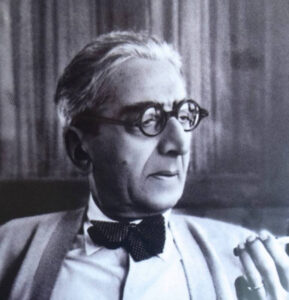

Mihail Jora (1891-1971)

Mihail Jora, alongside George Enescu, was a central figure in Romanian music in the first half of the 20th century. A renowned Romanian musician, composer and conductor, Jora became a full member of the Romanian Academy in 1955. He created numerous award-winning works reflecting his exceptional compositional talent, influenced generations of musicians and was a moral beacon in difficult times.

Born in 1891, Mihail Jora came from an old family of Romanian aristocrats, mentioned in Moldavian documents as early as 1392 as landowners, with Armenian connections in his maternal line. He was a cousin of Maruca Cantacuzino, wife of the famous George Enescu. His musical education began under the guidance of his mother, who had graduated from the Dresden Conservatory.

From the age of 10, between 1901 and 1909, he studied piano in Iași with Eduard Meissner, continuing between 1909 and 1912 with Hélène André. Between 1909 and 1911, Jora studied music theory and solfeggio with Sofia Teodoreanu and harmony with Alexandru Zirra at the Conservatory in Iași. Later, Jora furthered his studies in Leipzig, with teachers such as Robert Teichmiller for piano, Stefan Krehl for harmony, counterpoint and composition, Hoffmann for orchestration, Hans Sitt for conducting and Max Reger for composition. The outbreak of the First World War forced him to interrupt his studies in Germany. On his return to Romania, he was awarded the George Enescu Prize for composition. In 1916, once Romania entered the war, Jora joined the army, but in October of the same year he was seriously wounded and had a leg amputated, forcing him to spend two years in a sanatorium for recovery. After the war ended, between 1919 and 1920, he completed his musical education at the Paris Conservatoire, studying under Florent Schmitt. After his return to Romania, he became a pillar in the development of Romanian music, being a founding member of the Romanian Composers’ Society and a respected teacher at and even rector of the Bucharest Conservatory. He also conducted and was artistic counsellor at important institutions such as the Bucharest Philharmonic and Opera.

Mihail Jora composed balete, symphonies, chamber music and lieder, including “Curtea veche”, “Priveliști moldovenești” and “Burlesca”. He was a prominent representative and innovator of the lied in Romanian music, and it is interesting to note that he called his more than one hundred compositions of this type ‘Cântece’ (Songs), precisely to emphasise the autochthonous character and unique features that set them apart from the German lied tradition, represented in particular by the works of Schubert, Schumann and Brahms. He created numerous pieces based on the verses of famous Romanian poets, which stand out for their original expressiveness, richness and diversity in terms of content, often impregnated with humour and irony. His work is remarkable for the skilful realisation of the melodic and rhythmic elements specific to popular song. He was among the first composers to recognise the artistic potential of ballet.

During the communist period, Jora refused to subordinate his artistic creation to party ideology. He was dismissed and marginalised, but kept his integrity, resisting political pressure to turn music into a propaganda tool.

Jora’s pupils, such as Paul Constantinescu, Dinu Lipatti, Ion Dumitrescu, Mircea Chiriac and Pascal Bentoiu, became important figures in Romanian music themselves. Although the communist regime tried to minimise his contributions, Jora remained a revered figure for his talent and for his firm stance against political influences on art.

Mihail Jora left behind an impressive legacy, both through his musical creations and his example of moral integrity. Although not always officially recognised, Jora remains an important figure in Romania’s cultural history, appreciated not only for his music, but also for his courage to remain true to his principles.

Mihail Jora’s Little Suite op.3 for violin and piano, composed in 1917, is a cycle of miniatures in which one can notice consistent changes in the structure of the melody, which, throughout the suite, takes on increasingly pronounced national features. Thus, if in the first part, the music seems to betray Jora’s affinity with the Lied, through the musical idiom suggested to the violin, the next movement brings a solemn, oppressive atmosphere, like the anguish of an exile, if we were to refer to the chosen title (Bejenie). But the next movement gradually brings back the generosity of a diaphanous music exposed with jovial, playful tendencies.