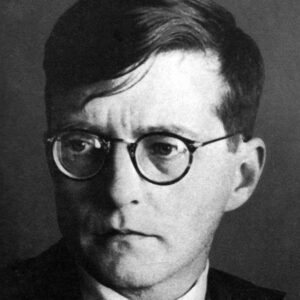

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Dmitri Shostakovich stands as a monumental figure in 20th-century classical music, considered alongside his contemporary Sergei Prokofiev as one of the most influential Russian composers of the Soviet period. Shostakovich’s musical contributions are immense and diverse his work often blending a subtle irony with genuine emotion, alongside a unique fusion of traditional and modern musical techniques and philosophies.

Born on 25 September 1906 in St Petersburg, Shostakovich’s upbringing in this city had a profound influence on his life and compositions. It is here where he began piano lessons with his mother at nine, quickly demonstrating remarkable talent. He often memorized pieces after only one hearing. This early promise led to his enrollment at age 13 in the Conservatory in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). Here, composer and teacher Alexander Glazunov oversaw his development, ensuring he had opportunities to compose and perform.

Much like Mahler, whom Shostakovich held in high regard, he employed a range of musical techniques, frequently showcasing stark contrasts and combining different moods such as despair and the grotesque. Remarkably, Shostakovich managed to craft a significant body of work while being under the watchful and often suspicious eyes of Soviet authorities. His life as a composer in 20th-century Russia was fraught with challenges, marked by a fraught and sometimes perilous relationship with the Soviet regime. A notable instance is his delightful, Haydn-inspired Ninth Symphony, which the authorities criticized as a trivial and inadequate response to the conclusion of World War II and Russia’s role in the defeat of Nazism.

His battle against political repression and the regime’s enforced adherence to propaganda was a constant struggle, making Shostakovich’s life story one of the most compelling and tumultuous in classical music history. Thus, his opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk”, initially successful, later criticized for its complexity in 1936, led to a challenging situation for Shostakovich, whose relationship with the Soviet authorities became tumultuous, when the Zhdanov decree targeted him for formalism and it happened again in 1948. All these accusations were part of broader Soviet campaigns against artistic styles deemed incompatible with Socialist Realism, the state-sanctioned artistic doctrine. “Formalism” in this context referred to music that was considered too complex and not accessible to the masses. Therefore, Shostakovich was forced to adapt his compositional style, often leading to self-censorship and strategic public compositions to align with Soviet expectations. Even so, he managed to hide his more experimental works, while navigating between maintaining artistic integrity and complying with state demands. Despite these challenges, he held various official positions and received several state awards.

For those new to Shostakovich, his Fifth and Tenth Symphonies are essential. Among his six concertos, four are frequently performed: the two Piano Concertos, the First Cello Concerto, and the First Violin Concerto. On the chamber music front, the gripping Eighth String Quartet vividly depicts the horrors of war. Other notable pieces include the Second Piano Trio and the Piano Quintet.

During the Cold War, Western critics often dismissed Shostakovich, labeling him as a banal composer who compromised his artistic integrity to survive under Soviet constraints. However, what truly stands out in Shostakovich’s music is its remarkable individuality. As a voice for the oppressed Soviet populace, he developed a distinctive musical language filled with brutal irony, intense anger, deep introspection, and feigned optimism. This language, while based on familiar models, was capable of nuanced expression.

Shostakovich’s style reflects the 19th-century Russian tradition, blending Tchaikovsky’s emotional intensity with Mussorgsky’s stark realism. He was also influenced by contemporaries like Stravinsky’s austerity, Prokofiev’s sardonic humor, and Alban Berg’s intense expressionism. The connection with Mahler is crucial, as both envisioned the symphony as an epic form that captures the essence of the world, juxtaposing the banal and the profound for dramatic effect. This Mahlerian contrast is at the core of Shostakovich’s work, enveloping the composer in ambiguity and duality. This duality is evident from his First Symphony, considered by many as the most sophisticated symphony ever crafted by a 19-year-old.

Shostakovich’s early success brought him international attention as a promising Soviet composer, with his works approached by renowned conductors like Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini. However, domestically, he faced challenges in realizing his potential. In the 1920s, amid a cultural atmosphere that seemed to favor a blend of revolutionary politics and Western avant-garde, Shostakovich aligned himself with modernists. This experimental phase produced several provocative works, including the satirical opera “The Nose” based on Gogol, music for Mayakovsky’s “The Bedbug,” and the film score for “New Babylon.”

While Shostakovich explored his talents in caricature, the introspective lyricism from the latter part of his First Symphony became increasingly prominent, notably in the haunting slow movement of the 1934 Cello Sonata. Premiered during a concert celebrating the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution, it was a resounding success, meeting the authorities’ expectations with its simpler musical language. Nevertheless, the audience interpreted the piece differently, recognizing its undertones of sorrow, suffering, and isolation, as noted by his close friend Mstislav Rostropovich.

This narrative of sorrow and isolation permeates Shostakovich’s later symphonies, such as the wartime Leningrad Symphony (No. 7), which he described as a requiem for the city devastated by Stalin and Hitler. The irreverent Ninth Symphony defied Stalin’s expectations of a victory symphony, while the Tenth Symphony’s demonic Scherzo is believed to be a musical depiction of Stalin himself. These themes are further explored in a more intimate setting in his cycle of 15 string quartets, which he began after the Fifth Symphony.

In his later years, Shostakovich faced health issues but continued to compose, with his later works reflecting a preoccupation with mortality. He joined the Communist Party in 1960, a decision interpreted in various ways. He passed away in 1975, leaving behind a significant musical legacy that haunts us with its sharp contrasts, elements of the grotesque that reflect his personal struggles and the political climate of the time. As a tribute to his towering music personality, The Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica, is named for him.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87 (1933) form a piano collection influenced by J.S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. This cycle includes a prelude and fugue in each of the 24 major and minor keys, mirroring Bach’s approach. Although this series is inspired by from Bach, Shostakovich’s composition is distinctivly his own, showcasing his unique harmonies, emotions, and musical concepts. In the 1930s, violinist Dmitri Tsyganov adapted 19 of these preludes for violin and piano, an endeavour praised by Shostakovich who remarked, that listening to this transcriptions, he used to forget that the Preludes were originally composed for piano because they sounded as if they were inherently suited to the violin.