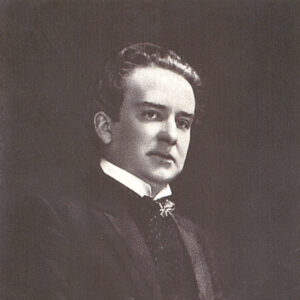

Sergei Edouardovich Borkiewics(1877-1952)

Sergei Edouardovich Bortkiewicz was born in Kharkov (Ukraine) on February 28, 1877, and spent most of his childhood on the family estate in Artyomowka, near Kharkov. Bortkiewicz studied music with Anatol Liadov and Karl von Arek at the Imperial Conservatory of Music in St. Petersburg. In 1900, he left St. Petersburg for Leipzig, where he became a student of Alfred Reisenauer, who in turn was a student of Liszt. By July 1902, Bortkiewicz had already completed his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory, where, upon graduation, he was awarded the Schumann Prize. Two years later, in 1904, he returned to Russia to marry Elisabeth Geraklitowa, a friend of his sister. Then, together with his wife, he returned to Germany and settled in Berlin, where he began to compose in earnest. Bortkiewicz continued to live in Berlin, but spent his summers in Russia visiting his family or traveling around Europe, often to give concerts. For a year he taught at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory in Berlin, where he met his lifelong friend, the Danish pianist Hugo van Dalen (1888–1967).

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 changed Bortkiewicz’s life. As a result of his assimilation into the Russian space, he was initially forced to remain under house arrest and then to leave Germany. He returned to Kharkov, where he became a music teacher, giving concerts at the same time. During these years in Kharkov, he composed the Cello Concerto Opus 20 and the Violin Concerto Opus 22. The end of World War I marked the beginning of the Russian Revolution, forcing the composer and his family to leave the Artyomowka estate, which fell to the Communists. In June 1919, the Communists retreated before the White Army and Bortkiewicz was able to return and help manage the family estate, which had been completely plundered. This situation did not last long, however, because, while he was in Yalta on a trip with his wife, the fall of Kharkov to the Red Army made it impossible for his family to return to Artyomowka. Bortkiewicz tried to leave Yalta and on November 20, 1919, he managed to obtain a pass on the ship “Konstantin”. The next day Sergei and Elisabeth Bortkiewicz arrived in Constantinople. Bortkiewicz was ruined: “I had 20 dollars in my pocket and that was all. The 1.5 million Russian rubles were worthless! I had only two suitcases of clothes, some underwear and my manuscripts.”

In Constantinople, with the help of the Sultan’s court pianist, Ilen Ilegey, Bortkiewicz began to give concerts and teach again. He became known among the embassies and met the wife of the Yugoslav ambassador, Natalie Chaponitsch. She organized musical meetings for Bortkiewicz at the embassy. Despite the good living conditions in Constantinople, Bortkiewicz dreamed of returning to Europe. With the help of Ambassador Chaponitsch, the composer and his wife reached Sofia via Belgrade, where they had to wait a while to obtain a visa for Austria, and finally, on July 22, 1922, they arrived in Vienna.

Between December 1922 and Easter 1923, Paul Wittgenstein (1887–1961), pianist and brother of the famous philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who had lost the use of his right arm during World War I, approached Sergei Bortkiewicz to compose a piano concerto for the left hand only. Around the same time, Wittgenstein approached Paul Hindemith, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Franz Schmidt with the same request. Later, Richard Strauss, Sergei Prokofiev, and Maurice Ravel, among others, were also asked to compose concertos that Paul could perform in public. As part of the agreement, each composer had to ensure that the entire score and orchestral parts would be owned in full by Paul Wittgenstein, who would have exclusive performance rights to the works for his lifetime. For this reason, Paul Wittgenstein refused to allow other pianists to perform some of the works he had commissioned. This happened to Siegfried Rapp (1915–1982), who had lost his right arm during World War II. Wittgenstein wrote to him on 5 June 1950: “You don’t build a house for someone else to live in. I commissioned and paid for these works, the whole idea was mine […] But those works for which I still have exclusive rights to perform will remain mine as long as I play in public; that is fair and just. When I die or stop giving concerts, the works will be made available to everyone, because I do not intend to let them gather dust in libraries to the detriment of the composers.”

Even today it is almost impossible to obtain unpublished works commissioned by Wittgenstein from his archive.

This is the main reason why the score of Bortkiewicz’s second concerto was never published and fell into oblivion after the composer’s death in 1952 and Wittgenstein’s in 1961. The premiere of Bortkiewicz’s Concerto No. 2 took place on 29 November 1923 in Vienna. Paul Wittgenstein played the piano and Eugen Pabst conducted.

With the help of his compatriot Paul de Conne, Bortkiewicz obtained Austrian citizenship in 1925. Grateful for the help he had given him, he dedicated his Third Piano Concerto Opus 32 Per aspera ad astra to Paul de Conne. The premiere of this concerto was scheduled for June 1927. The Russian pianist Maria Neuscheller took the solo part, and the composer conducted the orchestra.

In 1929, Bortkiewicz returned to his beloved Berlin, but the economic crisis and the rise of the Nazi regime caused him great problems, not least financial. He often asked Hugo van Dalen for help, which the pianist gave him unconditionally. On 21 April 1933, Bortkiewicz wrote to Dalen: “After the Hitler revolution almost all the opera producers, many orchestra conductors and others were removed and now new people have come in their place, with whom I must negotiate again regarding my work. […] Although I have a good reputation in Germany, I am still a foreigner and now those who are not true Germans are looked upon unfavorably and there are even fewer opportunities for any position.”

In 1933, Bortkiewicz was forced to leave Germany again. Because he was assimilated into the Russian space, he was persecuted by the Nazis and saw his name erased from all musical programs. He returned to Vienna where he settled at Blechturmgasse 1 in 1935 and, most importantly, he met his host, Maria Cernas, who looked after him and his wife with a deep sense of friendship.

To earn some money, Bortkiewicz translated from Russian into German the letters between P.I. Tchaikovsky and Nadeschda von Meck. These letters were published in 1938 under the title Die seltsame Liebe Peter tschaikovsky’s und des Nadjeschda von Meck (Köler & Amelang, Leipzig, 1938). Van Dalen adapted Bortkiewicz’s book for Danish readers and published it under the title Random Tschaikovsky’s vierde symphonie (De Residentiebode, 1938).

World War II was also a difficult time for Bortkiewicz and his wife. On December 8, 1945, he wrote to his friend, Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven, telling him how he was living: “I am writing to you from my bathroom where we huddled together because it is small and can be heated with a gas lamp (!) The other rooms cannot be used and I cannot touch my piano. This is it now! What awaits us next? Life is becoming more and more unpleasant, more merciless. I teach at the Conservatory at a temperature of 4 degrees, soon even lower! […]”

World War II brought Bortkiewicz to the brink of despair and ruin. Most of his printed compositions, which were owned by his German publishers (Rahter & Litolff), were destroyed in the bombing of German cities, and he consequently lost all his income from the sale of his music.

To celebrate Bortkiewicz’s 70th birthday, Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven (1883-1962) founded the Bortkiewicz Gemeinde (Bortkiewicz Society) whose purpose was to encourage the performance and dissemination of Bortkiewicz’s works.

After his retirement in 1947, the community of Vienna awarded Bortkiewicz an honorary pension. After 1947, and mainly due to the war years, Bortkiewicz’s wife was diagnosed with manic-depressive illness, which was a source of deep concern for the composer. Nevertheless, the composer’s success continued, and on 26 February 1952 the Bortkiewicz Gemeinde together with the Ravag Orchestra celebrated the composer’s 75th birthday with a concert at the Musikverein in Vienna. This was to be his last major concert, and the excitement of this event was illustrated in a letter of 18 March 1952 that the composer wrote to Hugo van Dalen: “I finally had the opportunity to show, in a large hall, with a large orchestra and soloists, what I can do. Not only the critics, but also those who know me were surprised and delighted […] I feel happy to be able to enjoy this recognition at the age of 75, a recognition that comes in most cases after the death of someone who has truly earned it […]”

Bortkiewicz had been suffering from a stomach ache for some time and, on the advice of his doctor, decided to undergo surgery on 23 October 1952. He did not recover and died in Vienna on 25 October 1952. Bortkiewicz was buried on 4 November 1952 at the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna. His wife, Elisabeth, died eight years later, on 9 March 1960, in Vienna. The graves of Bortkiewicz and his wife can still be found at the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna.

Bortkiewicz’ style

Bortkiewicz’s style was heavily influenced by Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, the early period of Scriabin and Russian folklore. He was not influenced by the musical trends of the 20th century. The impressive individual quality of the compositions, the melodic richness and the mastery of form characterize all his works. He wrote in a very “his” style that can be immediately recognized as “typical Bortkiewicz”. In addition to an admirable lyricism, there is also an atmosphere of deep nostalgia, a longing for past joys. The emotional effect of this, mixed with strong melodic accents, makes his music attractive and charming to many listeners.

Thanks to Hugo van Dalen, his close friend, we can enjoy Bortkiewicz’s music today and learn about his life from the many letters he sent to the Danish pianist. When Van Dalen died in 1967, his family bequeathed to the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague the manuscripts of several compositions, a written autobiography, Erinnerungen (darkenings), and a number of letters and scores, a collection that was later transferred to the Nederlands Muziek Instituut in The Hague. The Nederlands Muziek Instituut holds the only extant copy of the manuscript of the second piano sonata opus 60 and two preludes opus 66.

Seven decades after Bortkiewicz’s death, musicians around the world are rediscovering his music, and Bortkiewicz’s music is now being performed in his native Ukraine. Ukrainian conductor Mykola Sukach is working hard to revive interest in the composer and is seeking every possible way to promote his music. In recent years, pianists such as Stephen Coombs (Hyperion), Jouni Somero (FinnConcert Records) and Klaas Trapman (Netherlands Music Institute) have contributed to the rehabilitation of Bortkiewicz’s music. In 2008, pianist Lloyd Buck obtained permission from the Bath Museum to record a CD of Bortkiewicz’s music on the famous “Rachmaninov Piano” – the Steinway grand that Rachmaninov chose and used in his performances on his tour of the UK.